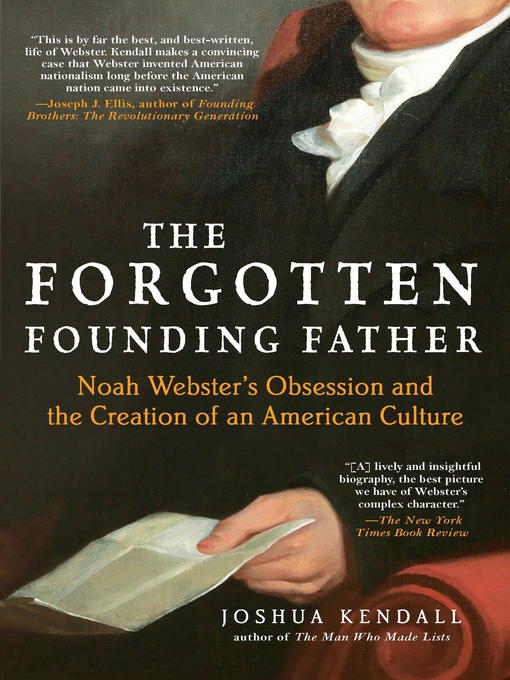

Webster hobnobbed with various Founding Fathers and was a young confidant of George Washington and Ben Franklin. He started New York's first daily newspaper, predating Alexander Hamilton's New York Post. His "blue-backed speller" for schoolchildren sold millions of copies and influenced early copyright law. But perhaps most important, Webster was an ardent supporter of a unified, definitively American culture, distinct from the British, at a time when the United States of America were anything but unified-and his dictionary of American English is a testament to that.

- Most popular

- Always Available Classics

- Available now

- New eBook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Try something different

- Best Food & Cookbooks

- Are you a Library Book? Cause I'm Checking you Out

- Rainbow Reads

- See all ebooks collections

- Available now

- New audiobook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- Rainbow Reads

- See all audiobooks collections

- Travel & Outdoor

- Home & Garden

- Food & Cooking

- Health & Fitness

- Sports

- Celebrity

- News & Politics

- Fashion

- Culture & Literature

- Tech & Gaming

- Art & Architecture

- Business & Finance

- Hunting & Fishing

- See all magazines collections